Effective Strategies for Planning Rotational Grazing on Your Farm

Introduction

Rotational grazing isn’t just for big dairy outfits with ten reels and a quad. On a small or medium-sized Irish farm, it can be the difference between chasing your tail all summer or finally feeling like you’re one step ahead of your land. Whether you're running beef, sucklers, or even sheep, putting a bit of structure on your grazing can help your grass grow better, your animals thrive, and your own workload feel a bit less chaotic. The key? Start with what you have, plan smart, and build from there.

Why It Makes Sense Financially

You’d be surprised how much grass gets wasted when animals graze freely across a field. With a basic rotational system, you’re giving the land a break and letting grass recover properly. Teagasc figures show grass use can jump from around 55% up to over 75% with rotation. That’s a decent bump. On a 30-acre platform, it could mean 30 extra tonnes of dry matter a year—easily saving you over €1,000 in bought-in feed if you’re making your own bales.

Cattle do better on it too. They’re getting lush, leafy grass more often, not picking through half-trodden stuff. It’s common to see an extra 150–200g a day liveweight gain with good rotation. That adds up over a season.

Layout: Design It to Fit Your Land, Not the Textbook

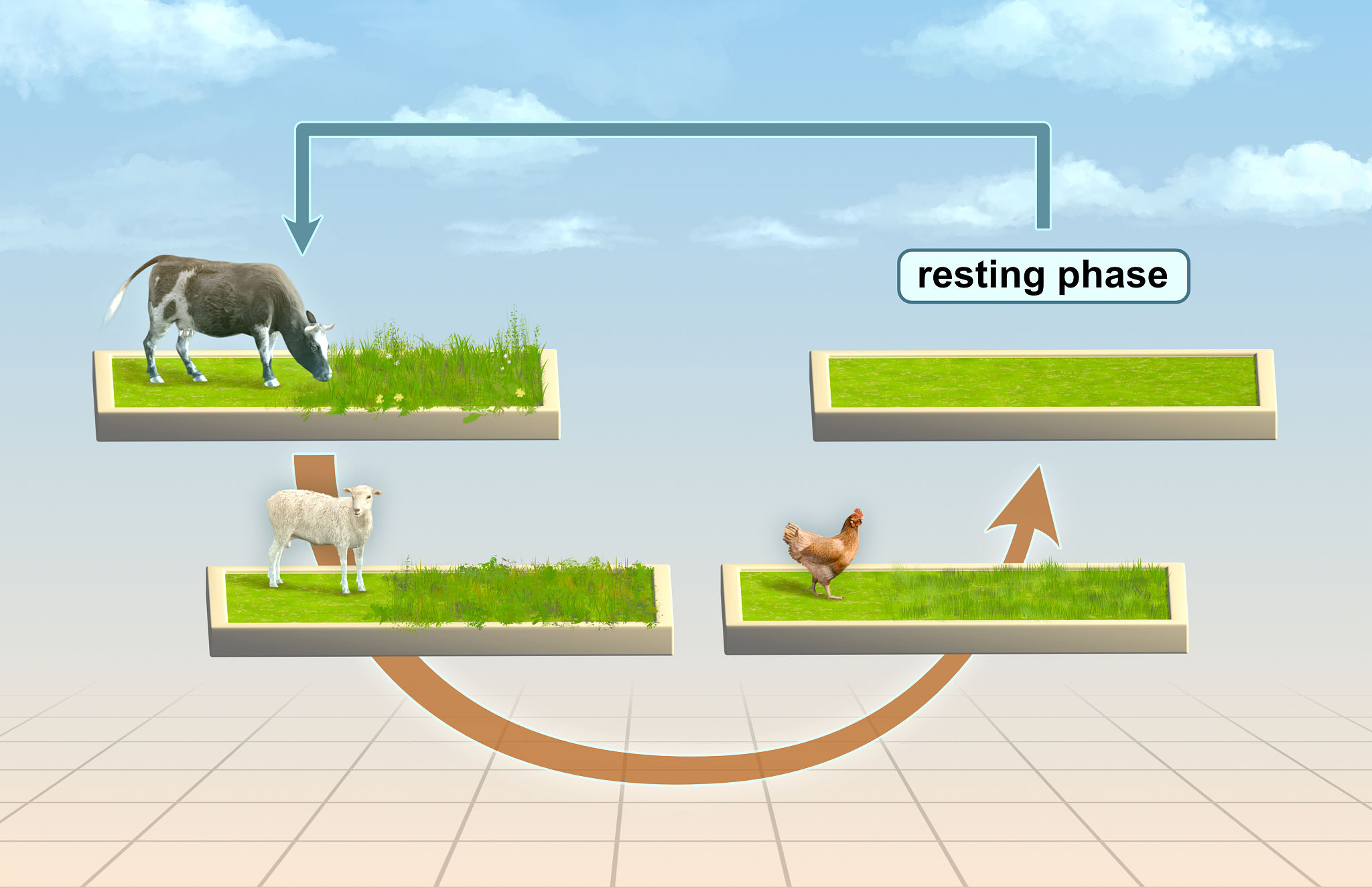

Every farm is different, so don’t get caught up in some perfect paddock plan you saw on YouTube. For a typical 40-acre farm running 40–45 head of cattle, aiming for ten paddocks plus a sacrifice paddock near the yard is a solid starting point. That might mean dividing your land into 3.5 to 4-acre sections, moving stock every 3–4 days, and allowing 30–35 days of rest during mid-season.

Start with a rough sketch using an aerial map—Land Direct is handy for this. Think about where the water is, how you’ll access each paddock, and how the land lies. Long fields are best split across the width to avoid long walking distances. Try to keep raceways central, especially if you’re herding solo. Begin with temporary wire and posts to test out your layout before committing to permanent fencing.

Fencing: What Works, What’s a Waste

You don’t need to spend a fortune to get started. A few reels of polywire, 100 step-in posts, and a decent fencer, battery or solar-powered, will cover most needs. A basic setup might cost between €500 and €1,000, depending on the size of your block. For cattle, one strand of polywire at chest height is usually enough, though younger stock might need two. Watch out for low-quality posts that bend or snap easily in dry ground, and make sure your fencer packs enough punch, underpowered units cause all sorts of grief when animals stop respecting the wire.

Keep your fencing flexible. Run temporary wire inside the permanent fence line to give you a chance to experiment with paddock sizes and flow before investing in permanent divisions.

Water: The Most Common Bottleneck

One of the most overlooked parts of any grazing system is water access. If your animals can’t get enough to drink, their performance suffers, no matter how good the grass is. In warm weather, cattle can drink up to 70 litres a day each—more if they’re milking or finishing. That puts a serious strain on under-sized pipes or slow-filling troughs.

Portable troughs with quick-connect fittings are a lifesaver on smaller farms. They’re cheap, easy to move with the reel, and prevent wear on one water point. If you prefer something more fixed, installing drinkers at the junction of multiple paddocks is a good compromise. For anything more complex, like a ring main system, be prepared to spend upwards of €1,000–€3,000, depending on pipe length and fittings. Just don’t skimp on pipe diameter, go for 25mm or 32mm if you’re servicing more than 20 animals at once.

Managing the Rotation: Grass Covers, Rest Periods, and Timing

Timing your rotation isn’t guesswork, it’s about knowing your growth rates and walking your ground regularly. In spring, grass can grow 30–70kg DM/ha/day, which means your rest period can be shorter—18 to 21 days is usually enough. By mid-season, you’re looking at 21 to 28 days, and in late summer, stretches of 30 to 35 days help keep covers up.

You want to graze grass when it’s at 1,200 to 1,600kg DM/ha. Go in too soon and you reduce yield. Leave it too late and you sacrifice quality. Try not to graze below 4cm, that’s where root systems weaken, and regrowth slows right down. If you find yourself ahead of the grass, cut surplus paddocks for bales. If you’re behind, stretch the rotation slightly and buffer with silage. This system doesn’t need to be rigid, it just needs to respond to what’s growing under your feet.

What It Looks Like in Year One

In the first season, you don’t need to go full throttle. Start by splitting half your platform into six to eight paddocks using reels and polywire. Monitor regrowth—use your boots and eyes rather than apps. If it’s working, expand to ten paddocks by midsummer. Use one paddock close to the yard as a 'sacrifice' area during poor weather or times of pressure.

By year’s end, you’ll have a clearer idea of what works. Maybe some paddocks need resizing. Maybe one water point isn’t enough. That’s fine—this is a system you adapt as you go.

Common Mistakes (and How to Avoid Them)

A few pitfalls crop up time and again. First: waiting for everything to be perfect. Start small and improve. Second: ignoring water. Do your trough setup before stock go in, not after. Third: having too few paddocks. If grass doesn’t get a decent rest, the rotation fails. Fourth: overgrazing. It’s tempting to leave stock on an extra day, but the damage takes weeks to undo. And finally: having no emergency plan. Always keep one field or paddock in reserve for when the weather turns or machinery breaks down.

Conclusion

Rotational grazing is about putting structure on what you’re already doing. With a bit of planning, some cheap gear, and a willingness to tweak things as you go, you’ll see better grass growth, healthier animals, and a smoother year overall. You don’t need a new system every year, just a good one that evolves with your land and your stock.

Start with what you’ve got. Make a few small changes. And before long, you’ll wonder how you ever grazed without it.

*By Anne Hayden MSc., Founder, The Informed Farmer Consultancy.